Cloud acquisition has been available for several years. iPhones and iPads running recent versions of iOS can store snapshots of their data in the cloud. Cloud backups are created automatically on a daily basis provided that the device is charging while connected to a known Wi-Fi network. While iCloud backups are great for investigations, there is one thing that might be missing, and that’s up-to-date information about user activities that occurred after the moment the backup was created. In this article, we’ll discuss an alternative cloud acquisition option available for iOS devices and compare it to the more traditional acquisition of iCloud backups.

iCloud Backups

iCloud backups are no longer cutting news. Cloud backups made their first appearance several years ago, and they improved significantly in iOS 9 (a reminder: binary authentication tokens no longer expire for iOS 9 and 10.x backups). Cloud backups contain most information available on the device. They are created once a day if certain conditions are met.

iCloud backups are great for forensic analysis. They are easily accessible, and they can be requested from Apple by following established procedures. One thing that’s not so great about cloud backup is the fact that they are created daily at best. In San-Bernardino case, the last cloud backup was months old; this was the reason for FBI to insist on unlocking the physical device.

However, there is another method that can deliver up-to-date information about the user’s activities straight from the cloud and without forcing anyone to break into the device itself.

Synced Data and Why It Matters

In addition to periodic cloud backups, Apple syncs certain types of data across iOS devices via iCloud. As an example, iPhones send information about phone calls and FaceTime conversations to iCloud just minutes after the call. Unlike iCloud backups, syncing occurs with or without Wi-Fi connectivity and whether or not the device is connected to a charger. In other words, the data will be synced on the go using available connectivity (including mobile data). In addition to call logs, iOS syncs Safari activities, notes, calendars and contacts.

One of the most interesting parts in this cloud sync is browsing history. iOS devices automatically sync Safari browsing activities with the cloud, saving information about open tabs and general browsing history. Similar to phone calls, these types of data are pushed to iCloud on a regular basis throughout the day, often just minutes after the user clicks on a Web link.

Interestingly, this feature is not clearly advertised by Apple. There is no clear, documented way to disable this syncing (apart from “not using the same Apple ID on different devices”, end of quote). Information is uploaded to Apple servers automatically if iCloud Drive is enabled on a given iPhone. Disabling iCloud Drive entirely seems to disable the syncing; however, some users reported that even turning off iCloud Drive did not disable the syncing for them.

About a month ago we released Elcomsoft Phone Breaker 6.20, giving it the ability to extract information about the user’s phone calls from the cloud. While we tried to make it clear that the data extracted was neither part of cloud backups nor Continuity artefacts, we still received mixed press on this feature. So why do we feel that iOS cloud sync is important?

Due to the obscurity of the feature, the chance that a criminal would have this cloud synchronization thing silently working on their device is higher than the chance of them maintaining a fresh cloud backup. In addition, the data is synced just minutes after the activity as opposed to iCloud backups being daily at best.

Retrieving Synced Data

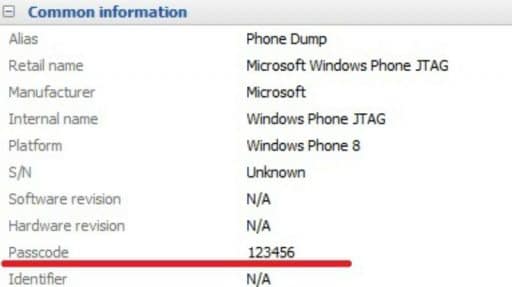

In order to access synced data, you will need to use Elcomsoft Phone Breaker 6.30 or newer. Once the product is launched, click on “Download synced data from iCloud” in the Tools > Apple, and follow the prompts.

The user’s Apple ID and password or iCloud authentication token are required to extract data from the cloud. Alternatively, you can use an authentication token to log in, which helps bypassing two-factor authentication checks.

Vladimir Katalov